========================================================================

Cybernetics in the 3rd Millennium (C3M) -- Volume 3 Number 6, Jul. 2004

Alan B. Scrivener --- www.well.com/~abs --- mailto:abs@well.com

========================================================================

[Note: you are receiving this issue of C3M 4 weeks late because I found

a problem with my bulk mail program that was failing to deliver about

15% of messages, and you were in the unlucky group. Hopefully I have

resolved the problem. Stay tuned for part 2 in afew days.]

Goof Gas

~ or ~

Holding the Dream Hostage

(Part One)

"Sorry we haven't been able to bring you up-to-date, but very soon

now the Cape will be shut back, terminating the North American

Effort in Space. Except, of course, for you..."

-- recorded message for returning astronaut

in the audio comedy "How Time Flys" (1973)

by David Ossman and the Firesign Theatre

( shop.store.yahoo.com/laughstore/daoshowtifl.html )

Thirty three years ago today, July 26, 1971, I saw a Saturn 5 rocket

lift off from Cape Canaveral, carrying Apollo 15 to the moon.

Today I showed my daughter a Quicktime movie of the science experiment

done by astronaut David Scott on that mission, proving that a feather

and a hammer fall at the same speed in the moon's vacuum.

( lisar.larc.nasa.gov/BROWSE/apollo.html )

It seems like I've always been a huge fan of space travel. I grew

up with the Space Age: I was 4 when Sputnik launched, 8 when Alan

Shepard flew, and 16 when Neil Armstrong stepped onto the moon.

I have a battered red backpack that has sewn onto it the mission

patches of the four manned space missions I have seen launch or land:

( www.well.com/user/abs/Cyb/4.669211660910299067185320382047/backpack.jpg )

( www.well.com/user/abs/Cyb/4.669211660910299067185320382047/backpack.jpg )

- Apollo 15, Saturn 5 launch, July 26, 1971,

Kennedy Space Center

- Columbia mission STS-1, space shuttle launch, April 12, 1981,

Kennedy Space Center

- Columbia mission STS-2, shuttle orbiter landing, November 15,

1981, Edwards Air Force Base

- Columbia mission STS-28, space shuttle launch, Aug. 8, 1989,

Kennedy Space Center

(

science.ksc.nasa.gov/shuttle/missions )

Or I should say the first four. On June 21, 2004 my family, some

friends and I witnessed the test flight of Burt Rutan's SpaceShipOne,

and pilot Mike Melvill's becoming the first person to reach outer

space (100 km) in a vehicle that wasn't launched by a government.

(This vehicle will competing in September for the Ansari X Prize,

a $10 million prize for the first vehicle to carry three humans up

to 100 km twice in two weeks.)

(

www.xprize.org )

For most of my life I have also been evolving towards a Libertarian

political perspective. Perhaps it began with my love of the feisty

science fiction of Robert Heinlein, in novels like "The Moon is a

Harsh Mistress" (1966).

(

www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/0312863551/hip-20 )

I remember in high school when I began learning the physics of heat

transfer, what they call "thermodynamics," and I came to understand

that 50% energy waste was the theoretical maximum efficiency of any

engine that turned heat to other forms of energy. Even then I had

the intuition that taxing people and then having the government pay

for things they could be buying directly was highly inefficient, like

those heat engines.

This point was subtly underlined by the comedy album "I Think We're

All Bozos On This Bus" (1971) Firesign Theatre.

(

www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/B00005T7IT/hip-20 )

At an EPCOT-like "future fair" an animatronic politician demonstrates

a "model government," powered by a "ton of coke," and then explains

"half a Watt comes in here, must go out there." Or -- punsters that

they are -- did he say "half of what comes here must go out there"

instead, completing the analogy between governments and heat engines?

What I gleaned from this was government = entropy.

Lately I have been casting about for an analogy that explains why

I am always nervous when the government tries to solve a problem.

Here's what I've come up with: suppose you're stuck someplace

with a room full of people and you have a migraine headache which

intensifies when there is a loud noise. "Please don't make noise,"

you ask of your companions. One of them stands on a chair and shouts

"Nobody make any noise!" You ask them not to do that, and then another

person starts banging garbage can lids together. "Don't stand on

chairs and shout!" they bellow. And so on. This is the way government

works, but instead of making noise, they spend money.

Maybe I'm getting this from a story line on the old "Rocky and

Bullwinkle" show in the early sixties called "Goof Gas Attack."

Master spy villain Boris Badenov gets ahold of a gas that makes

people stupid, and sprays it on Wasssamatta U., Bullwinkle's alma

mater. All of the professors are turned to idiots. Then he goes

on to Washington to spray the congress. But upon arriving he hears

a congressman say, "I propose a thirty million dollar study to find

out why the government is spending so much money." Boris decides

someone has beat him to it, telling his assistant, Natasha Nogoodnik:

"That IS goof gas."

(

www.toontracker.com/bullwink/bulleps.htm )

But the two areas where my Libertarian politics seemed to have a

blind spot were the environment (more on that in another issue of

this e-Zine) and space. For too long I have gone along mindlessly

with the assumption that our government should be in the space

exploration business.

Of course everyone with an awareness of history knows that John

F. Kennedy got us started down this road. He addressed a joint

session of congress on May 25, 1961, to ask for the money for the

moon shot, saying:

First, I believe that this nation should commit itself to

achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing

a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.

No single space project in this period will be more impressive

to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration

of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.

(Was he using the expense of the project as a selling point?)

But if you've seen any of the many documentaries and museum kiosk

displays that deal with this challenge, what you have usually seen

is an excerpt from another speech Kennedy gave on September 12, 1962,

at Rice University. He said:

But why, some say, the moon? Why choose this as our goal? And

they may well ask why climb the highest mountain? Why, 35 years

ago, fly the Atlantic? Why does Rice play Texas?

At this point the Rice attendees gave a big cheer. But the football

reference is usually edited out of the kiosk versions. Over the

roaring crowd (a far cry from his reception in congress, where they

had to figure out how to pay for it), he goes on:

We choose to go to the moon. We choose to go to the moon in

this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy,

but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to

organize and measure the best of our energies and skills,

because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept,

one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to

win, and the others, too.

(

www.cs.umb.edu/jfklibrary/j091262.htm )

(Yay!) This revisionism isn't too big a deal in and of itself, but

it is worth noting that NASA has been manipulating history for a while

now to inflate its perceived support.

[Aside: I almost wrote this month's e-Zine on the topic of "All I

Know About Operations Research I Learned from Theme Parks," about

my lifelong obsession with the Walt Disney Company and what it has

taught me about organizational cybernetics, but I decided the topic

at hand was more pressing, when I realized we'd just had the 35th

anniversary of the moon landing on July 20, 2004. I noticed a

coincidental connection between the two topics. John F. Kennedy

wen to Florida on November 16, 1963, to inspect progress on the moon

program at Cape Canaveral. A week later he was dead.

For more details see "Moonport: A History of Apollo Launch Facilities

and Operations" by Charles D. Benson and William Barnaby Faherty.

(

www.hq.nasa.gov/office/pao/History/SP-4204/ch7-7.html )

On the day of JFK's assassination, Walt Disney was flying over Orlando

and saw the freeway interchange of Florida's Parkway and Interstate 4,

and made the final selection of Orlando for his new Disney World

resort.

Walt Disney went to Florida in December of 1966 for a groundbreaking

ceremony for the new theme park. A week later he was dead.

For more details see "Married to the Mouse: Walt Disney World and

Orlando" (2003) Richard E. Foglesong.

(

www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/0300098286/hip-20 )

In both cases I am reminded of Moses getting to see, but not enter,

the promised land.]

Some of the most significant and formative events of my 20s were

the times I became disillusioned with ideas and institutions.

In the early 1970s I became disillusioned with politics, after

working on the 1972 George McGovern presidential campaign, which

he lost by a landslide to Nixon, and then finding out from Woodward

and Bernsteins's "All the President's Men" (1975) that McGovern

was the opponent Nixon wanted to run against.

(

www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/0671894412/hip-20 )

In 1976 I became disillusioned with the Walt Disney Company, by

becoming one of their employees at Walt Disney World. That story

I will tell later, but I do want to mention that on my first visit

to the Magic Kingdom I was quite astonished at the political content

of the Hall of Presidents attraction. The show, in a large, wide

theater, began with what looked like a multiscreen slide presentation

that stretched across five screens, covering 180 degrees, showing 100

color paintings of historic events, along with music and narration.

The first event highlighted was the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794.

(

www.americanrevolution.com/WhiskeyRebellion.htm )

From the show script:

Narrator: The first test was not long in coming. It occurred in

George Washington's second term as president, an incident known

as the Whiskey Rebellion. In colonial times, corn was an abundant

crop but difficult to transport. And for convenience was often

converted to distilled spirits. Since this important byproduct

was shipped from state to state, the federal government saw fit

to levy a tax upon it. But the people objected in principle, and

before long their opposition had flared up in riots. Here was the

first challenge to the federal authority.

Governor Mifflin: The question remains whether the President has

any legal right to use force.

George Washington: As to the legality of it, Governor Mifflin, I

have here an opinion from Justice Wilson advising that the courts

of your state are unable to deal with the crisis through ordinary

judicial proceedings. Under the law this would empower me to use

the federal militia.

Narrator: Fortunately, the rebellion ended without bloodshed.

The mere size of the militia overawed all further opposition.

Washington had shown his people that the government was prepared

to ensure domestic tranquility when necessary.

(

burnsland.com/hallofpresidents/script.html )

What surprised me was that rather obscure historic occasion -- when

George Washington first led federal troops against American citizens

-- was being trotted out as a great event in our nation's history.

(Interestingly, this was also the first time our citizens were called

"terrorists" by their government -- for harassing tax collectors.)

Immediately afterward the show embraces the bloodbath of the Civil

War as more evidence of increasing federal power, and that's a good

thing. The slide show ends with a clip of film, revealing that we

were watching underutilized 70mm projectors all along. Offered as

the ultimate justification for all this federalism is a movie, spanning

all 5 screens, of a Saturn 5 launching. Not a word is spoken, we are

just left to draw our own conclusions. It seemed to me similar to

the Fascists argument that we must form a bundle of sticks to be

strong enough to whack our enemies.

[This show has since ben "fixed" according to web sources:

In June 1993, the program was closed for a major overhaul in

program content. A new script, narrated by poet Maya Angelou

focused more on matters of racial tension through the years

than the original program had and was praised by some for

being more enlightened about the negative aspects of American

history. Others criticized it for being too politically correct.

(

waltdatedworld.bravepages.com/id223.htm )

I suppose that Civil Rights make a better justification for Civil

War than do feats of Civil Engineering.]

This stint at Disney World was in the middle of a bicycle journey with

my wife across America, and when the time came to quit our jobs and

hit the road again, we next made our way to Kennedy Space Center,

my first real visit. (The Apollo 15 launch had not included a tour.)

Since this was 1976, the Saturn had stopped flying and the shuttle

wasn't ready yet, so there wasn't much going on. In honor of the

US Bicentennial, they'd set up some geodesic domes in a parking lot

and invited representatives from industry in the present their visions

of the future. I remember a lot of hydroponics, and later when the

EPCOT theme park opened at Disney World it seemed like about the same

stuff. After a small dose of this future boosterism we went on the

KSC facility tour. I remember we were in the launch control room

(not mission control, that's in Houston at JSC) and we looked out over

the salt marshes at pad 39A, where the Apollo missions had blasted

off. Our tour guide pointed out that there were giant metal vertical

shutters on the windows. At the push of a button they all slammed shut,

protecting the launch controllers from the rocket's blast. "Boy,"

said my wife, "America has the most expensive hobby ever!"

While NASA was redesigning the shuttle to meet congress's repeated

demands that it be cheaper to build even if it would later be more

expensive to operate, The People were coming up with some pretty

interesting ideas about space. Most notably Princeton physicist

Gerard O'Neill and his students figured out that we could build

giant cities in earth orbit, also solar power satellites form about

the cost of the Alaska pipeline. His first published work on the

subject was in the magazine "CoEvolution Quarterly," published by

Stewart Brand's "Whole Earth Catalog" crowd. "CQ," which had also

published Paul Erlich of "Population Bomb" fame, and covered the

"limits to growth" waterfront, had an article in the Spring '76

issue by Peter Vajk called "Space Colonies, Ethics and People,"

which reran some of the earth simulations in "Limits to Growth"

with the addition of space colonies, turning our closed system

of planetary resources into an open system.

(

www.l5news.org/L5news/L5news7605.pdf )

Apocalypse was averted. I can't find the original article on-line,

but there is a follow-on as part of a book published by "CQ" in 1977

called "Space Colonies" which is now archived on-line by NASA!

(

lifesci3.arc.nasa.gov/SpaceSettlement/CoEvolutionBook/LIFES.HTML#Limits%20to%20Growth-wronger%20than%20ever )

[Also, the first thing I ever got published, a letter to "CQ," is in

the same archive under the title "Juvenile Space."]

(

lifesci3.arc.nasa.gov/SpaceSettlement/CoEvolutionBook/DEBATE1.HTML#Juvenile%20space )

* * * * * *

"If we can put a man on the moon, travel to Mars, examine the

intricacies of DNA, shouldn't we be able to figure out how to

get good teachers in hard-to-staff schools?"

-- Governor Mark Warner, Commonwealth of Virginia, speaking

at the 2004 National Forum on Education Policy, Orlando, FL

"The clear logical writings of Von Mises, Hayek, Bastiat and other

free market advocates convinced many people that politics was a

useful tool in the fight to reverse the encroachment of socialism

into our lives. The popular saying at the time -- 'If we can put

a man on the moon, we can eliminate poverty'-- terrified those of

us who realized the havoc unlimited social spending could cause."

-- "Gathering in the Name of Freedom" by Kathryn Augustin, Hostess,

Libertarian Party of Michigan Founding Convention

(

www.mi.lp.org/history/25thann.htm )

I wish I could track down the reference, but it was pre-web; somewhere

I read an "op ed" piece in a newspaper in the late 1970s that pointed

out that NASA was the poster-child for activist government, that is,

government out solving new problems. Every bureaucrat with a plan

needs NASA to be there, serving as the prototypical example, "If we can

put a man on the moon..."

But it didn't all sink in. Finally in 1981 the shuttle showed up, and

I had stars in my eyes again. My wife, three friends and I rented

a motor home and drove from San Diego to Florida to see the first

space shuttle launch. At the end of the ten day trip I had a better

understanding of what is what like to be cooped up in a capsule.

Our trip included space-related stops in Arizona,

(

www.noao.edu/kpno )

New Mexico,

(

www.spacefame.org )

Texas,

(

www.jsc.nasa.gov )

Florida,

(

www.ksc.nasa.gov )

North Carolina,

(

www.outerbanks.com/wrightbrothers )

Virginia,

(

www.larc.nasa.gov )

Washington, D.C.,

(

www.nasm.si.edu )

and Alabama,

(

www.msfc.nasa.gov )

but looking back 23 years one of the most memorable events occurred

on the second day out, at a little spot then called the Pima County

Air Museum, which wasn't even open when we stumbled on it.

(

www.aero.com/museums/pima/pima.htm )

You see, in preparation for the trip we had all re-read "The Right

Stuff" (1979) by Tom Wolfe,

(

www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/0553381350/hip-20 )

and so we knew that the first people to reach outer space weren't

astronauts but test pilots at Edwards Air Force Base, in the later-

canceled X-15 program, a vehicle which dropped from a larger airplane,

flew to the edge of space and then landed under its own power.

There on the Arizona desert, in an aircraft scrap yard that wasn't

even on display, on the other side of a chain link fence, we found

an X-15 fuselage. It looked so small. We videotaped it in the

twilight.

In 1983 I went to work for a company that traditionally had made

capacitors, but was branching out into high-tech. Three small

divisions had a telephone hold product for consumers, an

experimental ceramics oven for the space shuttle, and a 3D real-time

computer graphics system. I went to work for the graphics division,

which had about 4 people. The space oven group had about 20. Then

the CEO decided that the shuttle oven was a lost cause, because not

enough customers in industry wanted to use it, and he dissolved that

division. The graphics people moved into the space that the shuttle

oven people had occupied.

Later that year the CEO sent me to a local San Diego conference on how

to sell to the government. Most of the day was devoted to selling to

the Department of Defense (DoD), but there was one session on selling to

NASA. Here I learned something very interesting: that NASA was seen by

the aerospace community as a useful deflector of scrutiny for military

work. One speaker said: "Why do work for NASA? We usually only build

one or two of something, so you're not going to make money doing large

scale manufacturing on the back end. But every now and then you have

to let your guys out into the light. Give them a project they can talk

about to their wife and kids. Let them design something you can put

a model of it in your lobby."

I had no desire to do military work at this point, so I was perfectly

poised for my next disillusionment: with computer graphics. We were

working on a system with potential applications in Computer Aided

Design (CAD), entertainment, games, architecture, and education.

After an exhaustive marketing research project, management decided

the only viable near-term market for this box was military simulators.

Suddenly I was doing military work after all. I also remember that

1983 was the year Reagan announced the space station (I was exuberant)

and the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), called "Star Wars" by the

press, a potentially space-based missile defense (I was dismayed).

The company eventually sold boxes to the military airccraft divisions

of Boeing and McDonnell-Douglas, and the military avionics divisions

of Hughes and IBM. The only outfit not working directly on better

ways to kill people was Rockwell, who needed to simulates space

shuttles.

And so, in 1986, when I was choosing between which of GTI's customers

to go to work for programming one of the boxes, it was obvious I should

go to Rockwell, and work on the space station project; and so I was

to begin the process by which I became disillusioned with the space

program.

The first weird thing about working at Rockwell was that it was where

the shuttle orbiters were built, and they had their own "mission

control" room for launches, which I was hoping to get to see, but

two months before I was hired the Challenger blew up and the fleet

was grounded. The whole 22-month period I worked there the fleet

remained grounded.

The second weird thing was that recently Rockwell had been "suspended"

from selling stuff to the military due to incidents of time card fraud

in Texas, and management was EXTREMELY OBSESSIVE about having us fill

out time cards correctly. We had to attend mandatory training

sessions. But nobody was concerned about what work we did, with what

goals and milestones, or how fast, on what schedule, or how effective

or efficient we were. That's because Rockwell sold our time to the

government with a markup, and the longer we took, the more they made.

(That's where "cost overruns" come from.)

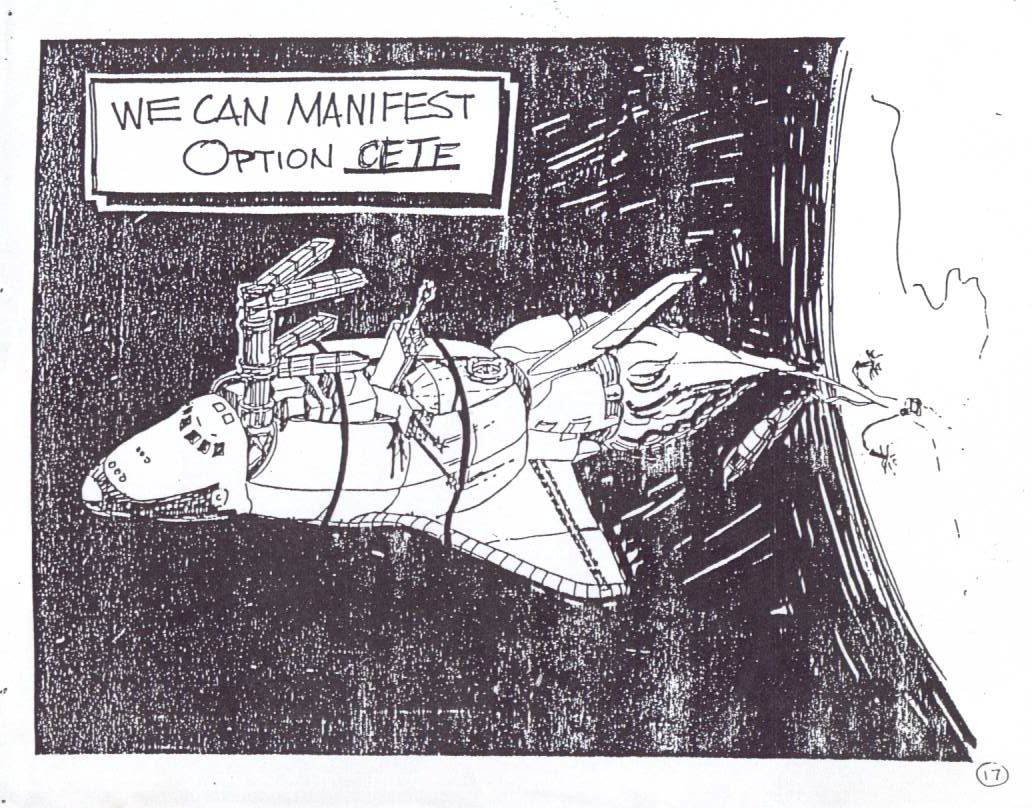

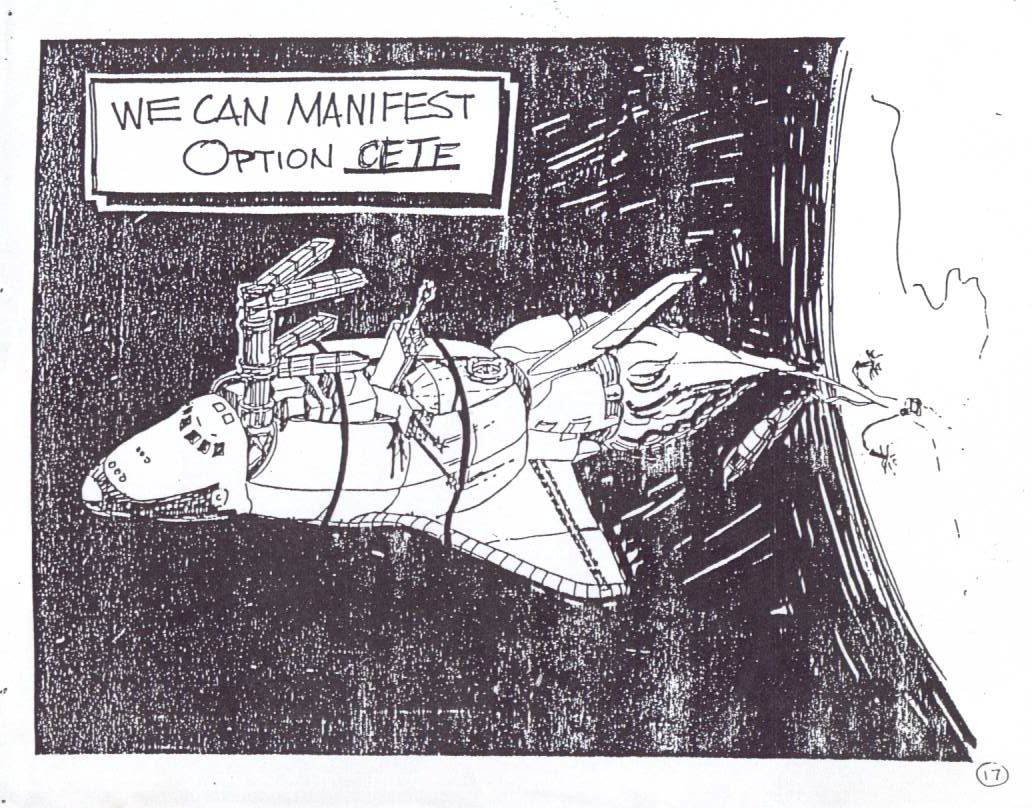

The third weird thing about working at Rockwell was that NASA had

asked us to put together an impossible plan. Rockwell as trying to

win a piece of the space station contract, and in our proposal to NASA

we had to put together a plan based on a "reference configuration" that

was modified and amended many times, but finally ended up being called

"option CETF" which was a grab bag of payloads from the many NASA

centers -- all of whom had powerful friends in congress - and as it

happened the total mass and volume were both beyond the shuttles

ability to carry to orbit. Some humorist with some pretty good

cartooning skills sketched and posted a drawing of an overpacked

shuttle held together with strapping like a busted suitcase,

with the caption "WE CAN MANIFEST OPTION CETF" stoking our optimism.

In other words, the competing contractors were being tested as to

our ability to tolerate B.S., or what Mr. T. calls "jibber jabber."

It reminded me of "goof gas."

(

www.well.com/~abs/Cyb/4.669211660910299067185320382047/CETF.jpg )

TO BE CONTINUED...

Follow-up to last month's e-Zine, "Six Degrees of Buddy Hackett":

- I meant to begin with this quote from "The Confusion (The Baroque

Cycle, Volume 2" (2004) by Neal Stephenson:

"The only cure for it is to become a merchant prince," said

Vrej Esphahnian, as they were sailing out of the Golden Gate

on a cold, clear morning. "And that is what we are working

toward. Learn from the Armenians, Jack. We do not care for

titles and we do not have armies nor castles. Noble folk can

sneer at us all they like -- when their kingdoms have fallen

into dust, we will buy their silks and jewels with a handful

of beans."

"That is well, unless pirates or princes take what you have so

tediously acquired," Jack said.

"No, you don't understand. Does a farmer measure his wealth in

pails of milk? No, for pails spill, and milk spoils in a day.

A farmer measures his wealth in cows. If he has cows, milk

comes forth almost without effort."

"What is the cow, in this similitude?" asked Moseh, who had

come over to listen.

"The cow is the web, or net-work of connexions, that Armenians

have spun all the world round."

Here Stephenson is delighting in drawing parallels in the 1600s to

our modern high-tech webs and networks.

( www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/0060523867/hip-20 )

- I also meant to work in this quote from "Excursions in Graph

Theory" (1980) by Gary Haggard (math subscripts changed to C syntax

due to lack of typesetting):

DEFINITION 2. Let G be a graph with p vertices, v[1], v[2],

..., v[p]. The p x p matrix A = a[i][j] is an "adjacency

matrix" for G if and only if for 1 <= i, j <= p we have

1 if (v[i], v[j]) is an element of edges of G

a[i][j] = {

0 if (v[i], v[j]) is not an element of edges of G

...

...if A is an adjacency matrix for a graph G with vertices v[1],

v[2], ... , v[p], then the (i,j-th) entry for A^n (the product of

A with itself n times) is the number of walks in G of length n

from v[i] to v[j].

I find this astonishing. And it completely over-solves the Seven

Bridges of Konigsberg problem.

( www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/0891010408/hip-20 )

- I got email from Jeff Sale, SDSU, on this topic:

After hearing you talk with Dave G. this past weekend about power

laws and social networks, it occurred to me that you may not be

aware of some ideas I've had for a long time about power laws in

learning, related to some ideas behind self-organized criticality.

... If you have time, take a look at:

www.banyantree.org/jsale/soc/

and:

www.banyantree.org/jsale/soc/critlrn6b.html

He finds some interesting patterns in how humans acquire skills.

========================================================================

newsletter archives:

www.well.com/~abs/Cyb/4.669211660910299067185320382047

========================================================================

Privacy Promise: Your email address will never be sold or given to

others. You will receive only the e-Zine C3M unless you opt-in to

receive occasional commercial offers directly from me, Alan Scrivener,

by sending email to abs@well.com with the subject line "opt in" -- you

can always opt out again with the subject line "opt out" -- by default

you are opted out. To cancel the e-Zine entirely send the subject

line "unsubscribe" to me. I receive a commission on everything you

purchase during your session with Amazon.com after following one of my

links, which helps to support my research.

========================================================================

Copyright 2004 by Alan B. Scrivener

( www.well.com/user/abs/Cyb/4.669211660910299067185320382047/backpack.jpg )

( www.well.com/~abs/Cyb/4.669211660910299067185320382047/CETF.jpg )

TO BE CONTINUED...

( www.well.com/~abs/Cyb/4.669211660910299067185320382047/CETF.jpg )

TO BE CONTINUED...