======================================================================= Cybernetics in the 3rd Millennium (C3M) Volume 12 Number 1, Jul. 2015 Alan B. Scrivener — www.well.com/user/abs — mailto:abs@well.com ======================================================================== In this issue: Spy vs. Spy appropriated to sell spy software (muzeum.llu.pl/konkurs/app-for-tracking/phone-spy-by-imei.html)

- Reboot Du Jour

- Uncrackable Encryption for the Masses

- "If It's Just a Virtual Actor, Then Why Am I Feeling Real Emotions?" (Part Six)

Reboot Du Jour

I know it's getting old, but I am yet again rebooting this eZine. Here's a few short subjects to begin:

a postcard promoting my new book, now on Amazon.com

- I wrote a book, and you can buy it on Amazon: "A Survival Guide for the Traveling Techie" (2014) by Alan B. Scrivener. ( www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/0974996815/hip-20 ) I also have a website to promote it, which desperately needs work. (Any web marketing folks out there want to give me a bid to fix it up?) ( travelingtechie.com ) And I'm even writing a blog, the "Traveling Techie Blog," to promote it as well. ( travelingtechie.blogspot.com )

- I spent most of 2014 consulting for a company called SynGlyphX, which uses 3D shapes called "glyphs" to display high-dimensional, complex spatial data in an intuitive way. The above video explains the concepts. The work is based on a public domain tool called ANTz. ( github.com/openantz/antz ) Also check out the SynGlyphX YouTube channel, ( www.youtube.com/user/SynGlyphX ) and my colleague Jeff Sale's site about ANTz at EdWorlds. ( www.edworlds.com/antz/toroids )

- Nora Bateson's awesome film "An Ecology of Mind," which I have spoken highly of before, is now on Vimeo. ( vimeo.com/ondemand/bateson )

- I received an email from Anna Chekovsky (about a year ago) letting me know she translated my 1993 article for the Medicine Meets Virtual Reality conference, "The Impact of Visual Programming in Medical Research," into Swedish. ( www.teilestore.de/edu/?p=1384 )

IATSE logo

- Follow Up to "What Just Happened?" in C3M volume 11 number 1. ( www.well.com/user/abs/Cyb/archive/c3m_1101.html#sec_1 ) Shortly after I wrote the article, about Samuel L. Jackson and the Academy Awards dissing digital artists at the 2013 Oscars, I attended the 2013 international conference on computer graphics and interactive techniques, commonly called SIGGRAPH, held in Los Angeles July 21-25. ( s2013.siggraph.org ) On the exhibits floor I found a booth for the labor union known as IATSE, the InternationalAlliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, which as it turns out is making a full court press to be the union of digital artists and animators for the movie and television industries. ( iatse.net ) I spent some time talking to the representative in the booth, especially about the events of the 2013 Oscars. He confirmed what I suspected, which is that many actors, including Mr. Jackson in particular (according to a conversation this gentleman had been a party to), feel that their craft is in danger of becoming extinct, or at least marginalized, due to computer graphics technology. He and I agreed that this is absurd. After all, for example, why does Pixar keep hiring big stars to do voices, instead computer generating them? Because only a human can give the kind of emotional performances audiences want to experience. Those of us inside the CGI industry understand this, but unfortunately some actors have believed the unrealistic prognostications that have been around since the 1980s, predicting complete replacement of actors by VActors (see the article at the end of this 'zine for more detail). If you ask me, the real tragedy is that the digital artists and animators, who are also human beings, are not getting the credit they deserve. The are still considered "below the line" employees, meaning they are not believed to contribute creatively, but only provide necessary grunt work, like a grip does. This is a modern scandal. While I don't generally see the benefits of unionization in the tech world, I am coming around to the viewpoint that in union-dominated Hollywood the Johnny-come-latelies in the computer industry need union protection to get the respect they deserve, as well as screen credits, benefits like overtime and pensions, and often even just to get paid. More on this as I become aware of it.

Uncrackable Encryption for the Masses

Captain Midnight decoder ring (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Secret_decoder_ring)

"The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized." — Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution, 1792 ( en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fourth_Amendment_to_the_United_States_Constitution )

|

|

Problem Statement

You've seen the news about the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) copying all the emails it can get its hands on, bad guys breaking into servers at SONY Corporation and spilling corporate secrets, and most recently the Office of Personnel Management of the U.S. government admitting they've had records of tens of millions of federal employees "hacked" — all events which have triggered a renewed interest in internet security. Today I want to tell you about a technique that can be used to solve the first problem, but not the other two. Uncrackable encryption can ensure that no matter how long the NSA keeps your email, and how advanced computers become in the future, they will never "crack" your encrypted data. As far as keeping bad guys from compromising your computers, that's a discussion for another day. (One solution to that involves custom hardware which can only run apps off a CD or other non-rewritable memory, also known as "breaking the Von Neumann Model.") So, to be clear, the problem statement is: in electronic communication between two parties who trust each other, how can they send data files between them that are encrypted in such a way that no one else can decrypt them?A Menagerie of Analogies

Asking around, I've discovered that a lot of people find encryption to be very mysterious, so I'm going to proceed by a series of simple analogies.

antique lock box with key, circa 1800

antique lock box with key, circa 1800

(http://hygra.com/uk/wb2/wb119/)

Analogy #1: The lock box. Most people understand the lock and key, an amazingly digital technology from the analog era. If I give you a lock box and send you to see Alice, who has the key, you can't see what's in the box unless you pick the lock or break the box. This is the promise of encryption, that someone — or some mechanism — can carry an encrypted message, but no one who possesses it will be able to read it without the encryption key that allows it to be decrypted back to its "plaintext" form.

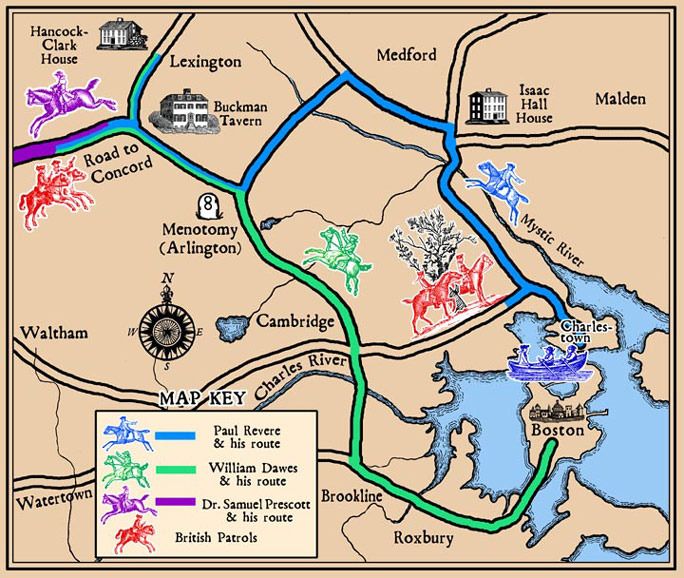

the routes of Paul Revere and associates

the routes of Paul Revere and associates

(thehistoricpresent.wordpress.com/2011/08/15

/what-does-one-if-by-land-two-if-by-sea-mean/)

Analogy #2: "One if by land, two if by sea." Most every

schoolchild in America knows the story of Paul Revere's ride, warning the

Minutemen that the British were coming, and how a signal in the tower of the

Old North Church revealed their route -- "One if by land, two if by sea." Though

anyone in Boston could see the lights in the tower (did you remember that there

were two?) only those who knew the code could interpret them.

But what if the secret of the code got out? The British (or anyone else) could

know what the colonists knew. A more sophisticated code would work this way:

on the morning of the ride the signaler ( sexton Robert Newman ) could flip

a coin, and use this formula:

- if heads, use "one if by land and two if by sea"

- if tails, use "two if by land and one if by sea"

A Menagerie of Cyphers

"Once I had a secret code, Where A was B, and B was G. G was K, and K was J; And J was M, and M was P. V was X, and X was V, And U was I, and I was U. 87 stood for Z, And 2 for T, and T for 2. O was 12, and Q was 17; I still don't know what those numbers mean. That is how we won the war; My secret code's no secret anymore. H was 9, and S was 33; Oh, how that confused the enemy! Then a recent survey showed That I don't understand my secret code." — "Secret Code" (parody of "Secret Love") by Allan Sherman, 1953 ( www.youtube.com/watch?v=rdrN9lOw6po ) ( www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/B003SWFLYW/hip-20 )So let's talk about ciphers for a minute. Any encoding technique which substitutes one symbol for another is called a cipher. Fans of the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey may recall that clever viewers spotted the fact that the name of the murderous computer, HAL, could be transposed to IBM just by bumping each letter up to the next one in the alphabet (and from Z to A to wrap around). This is a trivial cipher, and not worth using unless perhaps if you're trying to confound children. This type of cipher is know as as a ROT1 since the letters are "rotated" by one. ( listverse.com/2012/03/13/10-codes-and-ciphers/ ) shift by 1 (ROT1) A -> B B -> C C -> D ... Y -> Z Z -> A You can add a little complexity by bumping up by a different number than one (and of course you must again wrap around from Z to A if you go beyond the end of the alphabet.) This is essentially the encryption technique provided by the famous Captain Midnight (above) and Little Orphan Annie decoder rings of yore. It is called the Caesar cipher, named after Julius Caesar, who used it in his private correspondence. ( en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caesar_cipher ) shift by 4 (ROT4) A -> D B -> E C -> F ... Y -> C Z -> D The next step in increasing complexity is to have each letter encode as another in some scrambled way, instead of having each "mapping" be by shifting all the letters by the same amount. (Allan Sherman's song, "Secret Code," describes such a cipher in the lyrics quoted above.) scrambled A -> M B -> K C -> Y ... Y -> D Z -> N It might seem like this would make a pretty good cipher, but actually it wouldn't. The table above is considered the "key" to the cipher, and this case the key is one letter long — it is applied to each letter the same way. This means that every time a letter in the plaintext is repeated, the encrypted letter will also always be the same. This makes it possible to find patterns in the message. The historical novel "Cryptonomicon" (1999) by Neal Stephenson has a passage in which such s cipher is quickly broken. ( www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/0060512806/hip-20 ) In World War II a group of Army recruits who are being screened for possible code-breaking talent are placed in a classroom with a chalk board, and an officer begins writing without addressing them.

"Reading from a notebook, [Commander Schoen] writes out the following in block letters:( www.euskalnet.net/larraorma/crypto/slide7.html ) If you have the same techie impulses I do you might like to attempt to break the code before you continue reading. * * * By doing a frequency analysis the character of Waterhouse quickly identifies 18 as standing for the letter E in the message, and goes on to solve it: "ATTACK PEARL HARBOR DECEMBER SEVEN" — which immediately earns him a place in the code-breaking team. A more complicated case is called a Vigenére cipher. In this case the shift is different for each character in the message, up to a point where the key repeats. Often a phrase is used to represent the shifts. The first time I ran across this technique was in a Hardy Boys book I read as a kid. The boys found a piece of paper covered in apparent gibberish, with the initials C.S.A. written across the page. They eventually figured, with the paper dated from the Civil War and the initials stood for "Confederate States of America" which was the encryption key. Using this key over and over they decrypted the message. In such an encoding each letter in the key represents a numeric shift in the letters: A is 1, B is 2, etc. So the first letter in the message is shifted 3 letters (C), the second letter is shifted 15 letters (O), the third letter is shifted 14 letters (N), etc. This kind of cipher is possible to crack using the same letter frequency techniques (though a computer is probably required) as long as the message is no shorter than the key. This brings us to the central lesson here: if the key is as long as the message, and the key is random, the cipher becomes uncrackable. Not hard to crack, not crackable only with powerful computers and a long time, but theoretically uncrackable.19 17 17 19 14 20 23 18 19 8 12 16 19 8 3 21 8 25 18 14 18 6 31 8 8 15 18 22 18 11Around the time that the fourth or fifth number is going up on the chalkboard, Waterhouse feels the hairs standing up on the back of his neck. By the time the third group of five numbers is written out, he has not failed to notice that none of them is larger than 26 — that being the number of letters in the alphabet. His heart is pounding more wildly than it did when Nipponese bombs were tracing parabolic trajectories toward the deck of the grounded Nevada. He pulls a pencil out of his pocket. Finding no paper handy, he writes down the numbers from 1 to 26 on the surface of his little writing desk."

The Magic of the Random One-Time Pad

the secure teletype between Washington and Moscow,

sometimes called the "red phone" though it was neither

(http://skeptics.stackexchange.com/questions

/4215/does-the-u-s-president-have-a-red-phone)

the secure teletype between Washington and Moscow,

sometimes called the "red phone" though it was neither

(http://skeptics.stackexchange.com/questions

/4215/does-the-u-s-president-have-a-red-phone)

"Any one who considers arithmetical methods of producing random digits is, of course, in a state of sin." — John Von Neumann, 1951( en.wikiquote.org/wiki/John_von_Neumann ) While current debates over encryption wrestle with "how strong is strong enough?" (a 512-byte key is often defined as "strong" encryption), the technique of using a random key as long as the message has been known since 1882, and has been in the public domain since the 1930s, when a 1919 patent expired. ( en.wikipedia.org/wiki/One-time_pad ) Of course, creating random numbers is a tricky business. The best definition of "random" is "unpredictable." But it is only possible to prove that a given sequence of numbers isn't random, not that it is. Still, human history provides a time-tested set of techniques, mostly associated with gambling. Coin flips, roulette wheels, dice, lottery balls and thorough card shuffles have been used for a long time without problems (in the absence of cheating) to create fair games of chance. The above-mentioned "Cryptonomicon" describes secretaries at the legendary Bletchley Park in England in World War II drawing pieces of paper to create random keys for one-time-pad codes used by allied military codes. The big problem is that these techniques are labor-intensive. Recently, hardware random number devices have become popular, using various types of electronic, thermal or quantum noise to generate random numbers, which at last allows the process to be automated. ( en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hardware_random_number_generator ) It must be emphasized, as Dr. Von Neumann warned us, that using an algorithm or formula — which is a repeatable process — cannot produce random numbers; that is why these techniques are called pseudo-random. Recent advances in the mathematical field called chaos theory have yielded a better theoretical understanding of how the traditional gambling techniques actually work, but the best evidence of their effectiveness is that people keep using them. Both sides in World War II used this technique for some secure communications, and when used properly these codes were never broken. In the 1960s when the US and the USSR implemented the so-called "red phone," a teletype system was combined with paper tapes of random numbers, identical at both ends, to ensure secure transmission. (I was surprised to learn that the system was never used for any "real" communication between the superpowers; only test messages consisting of quotes form American and Russian literature were sent back and forth.) Believe me when I tell you that a message encoded with a truly random one-time-pad can not be "cracked" by any cryptanalysis technique, now or in the future. If the NSA is collecting citizen emails and archiving them against the day when future techniques have evolved to allow them to be read, this approach will not do any good, ever, with randomly encrypted communications.

How Do I Prove This To You?

(www.andertoons.com/science/cartoon/5710/what-hell-that-supposed-to-mean) Oops. It's really easy for me to say "believe me," but how can I make you believe? I'm trying to get people to make decisions that affect the security of their business dealings, and that takes some proof. I realize I have a mathematical mind, and that makes me an outlier. You can prove things to me with math, but I don't think that's the case for most people. Still, I'm going to try. Let's go back to the "one if by land" analogy. Forget the land and sea part; imagine instead that someone in the Old North Church needs to communicate a message to Paul Revere every night, about some tactical fact in the Revolutionary War, a fact that can be represented by a yes/no message, what we call in the cyber age a single "bit." If the British saw one or two lights in the church tower every night, and they also could find out the message later, like whether an army attacked, they might be able to figure out the code — but not if a coin flip was being used to determine the encoding. Without seeing the smudged coin they would have no way to infer what one or two lights meant. But it gets better. If Paul Revere were arrested by the British and they demanded to know the code, he could tell them either scenario: the one for heads or the one for tails. In other words, he could force the message to seem to be whatever outcome he wanted by manipulating the key. Now, consider that a random one-time-pad code is just a series of one-bit messages just like this strung together. Each random bit is independent, which means if you figure out one of them it doesn't help you with the others. This means that, like with Paul Revere, if someone demands the key you can force the message to seem to be whatever outcome you want by manipulating the key. This was the essence of Claude Shannon's proof in the 1940s that the code is uncrackable. With any cipher that repeats the key there is an ability to guess and then see if your guess is right. The key has to fit in a number of places, and so a wrong guess is easy to eliminate. Since with a one-time-pad you can pick a key to decrypt a code message into any plaintext (of the same length), there is no way to verify or disprove any guess of the key. (A little more detail: if you have an encoded message, usually called the ciphertext, you can make it seem to decode to any fake plaintext of the same length by performing an exclusive or operation on the ciphertext with the fake plaintext, which will yield a fake key. Anyone using this fake key on the ciphertext will get the fake plaintext. This was the substance of Shannon's proof of uncrackability.) Is this making sense?

The Trick Is Getting Everyone To Follow the Plan

"I usually go around speaking on the threat of the human element, particularly on social engineering." — Kevin Mitnick, famous cybercriminal( www.inspirationalstories.com/quotes/t/kevin-mitnick ) Okay, I'm going to warn you up front that this plan, as I present it, is a pain to implement. What you want is a system that is seamlessly integrated with email and other infrastructure, but since you and I don't control that, instead this is a bolt-on solution. And let's be clear what problem we're solving. With the system I describe, you can be confident that anyone intercepting any emails will be utterly unable to decrypt and read your messages (or look at your files, such a Excel spreadsheets) if all they have to work with is the traffic in and out of your network. This is not a plan for preventing cracking into your network, and stealing data, installing keyloggers and rootkits (look them up), or any kind of physical break-in resulting in theft of hardware and the data on them. But we need to solve one problem at a time. A reasonable use-case would be a company with a bunch of field offices, with the need for each office to email confidential company information, such as financial data, to headquarters every fiscal quarter so accounts can roll it all up into a quarterly report. To protect these files, which are infrequently sent between trusted parties, you would need this set of equipment, software and procedures:

- key generation — Somewhere at headquarters is a special computer used only for key generation. Ideally it has no internal hard drive and runs programs off Read Only Memory (ROM), and is not connected to the internet. A cage in the warehouse would be a good place, so it is easily observed. The computer could be a small Linux system like a Raspberry Pi, ( en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raspberry_Pi ) or a custom computer made with Arduino technology. ( en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arduino ) Its unmodifiable code would only do one thing: copy random bits from the hardware random number source and write them into two identical files on two USB drives, along with a key id number (a serial number for keys). A human operator would switch out the USB drives when they were full, and label them with both with the same serial number.

- key distribution — One copy of each key USB drive stays at headquarters while the other is delivered to a branch office. This is the most onerous part of the plan. They probably shouldn't be mailed, and using a commercial shipper would be iffy. A bonded courier is the best solution. (I'm imagining motorcycle couriers in black leather riding suits, but hey, that's just me.) This may sound like a big deal, but companies already must solve similar problems: how to deliver cash, confidential medical records, biohazard waste, etc. This could piggy-back off those efforts in some cases.

- message encryption — When an employee at a branch office wants to send an encrypted message, they plug in a key with enough random bits available and run a program to encrypt the file. This may be the same program as the decryption program listed below, or a separate program. The bits from the USB drive are used to encrypt the plaintext file (or any type of file) into an encrypted file. A straightforward approach is to use an exclusive or function. I have tested this and it works, both to encrypt and decrypt. ( en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exclusive_or ) A simple prototype program in the C language is on my web site. ( www.well.com/user/abs/Crypto/xor.ALL ) The program, for example, could take a Microsoft Word file, foo.docx, and create an encrypted version called foo.rotp (the rotp stands for Random One-Time-Pad). Then the program deletes the bits in the key file it just used from the USB drive. This is so they won't be re-used by mistake, and for security against crackers or subpoenas. The program also adds "garbage" bits to the end of the file to mask its true length. The sender then emails the encrypted file to a designated recipient as a standard attachment.

- file format notes — As a side note, the .ropt file will need

to contain the following fields in addition to the encrypted bits:

- the key serial number

- the start address in the key,

- the actual length of the input file,

- the file suffix (in this case docx) of the input file,

- a hash of the encrypted bits (explained below).

- message decryption — The designated receiver gets the email

with the attachment, saves it, and then runs the decryption program to re-create

the original file. Ideally the rotp suffix is registered with the operating

system so that the file can be simply "double-clicked" to perform this operation.

The decryption program must:

- locate the key file by serial number on a USB drive, or ask for it if it is not yet mounted,

- exclusive-or the key bits and encrypted bits to restore the plaintext file,

- delete the key bits used from the USB drive,

- check that the hash is correct,

- strip the garbage bits, and

- write out the plaintext file and restore the original file suffix.

Objections

I have been working with these ideas for nigh onto 16 years, and I've had time to think about the implications. I've also wandered into a few on-line forums on the topic, and know what kind of half-baked, as well as fully-baked, objections people have raised. I'd like to address a few here. It seems the format of a Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) list is the right way to proceed.Q: Nothing Is Perfect

That's not a question, but you're right. Still, every objection I've read to this system applies to all other encryption systems, and as far as I can see none is better.Q: How Can This Fail?

Mathematically the approach is quite airtight. Operationally, there are things users can do to damage the security. There have been numerous documented cases of a one-time-pad being "cracked" because users ignored directives and re-used the keys. Having the software delete keys as they are utilized reduces this risk, but like the man said, the problem with making things foolproof is that fools can be so ingenious. There is no realistic way to keep people from copying the USB drives with the keys on them and using them again, which defeats the whole point. It is also possible that the hardware random number generator can fail to produce random bits. More study of this is needed. And, of course, while the keys are being delivered bad guys could intercept them and copy them, making the whole exercise futile. This problem has to be solved on a case-by-case basis. Sealing the USB drives in envelopes with wax seals might help, as would having "tiger teams" attempt to compromise security. Kevin Mitnick, who does security testing now, says he has never failed to find a hole in security. It might be as simple as bribing or blackmailing a courier.Q: What If Something Goes Wrong and the Receiver Can't Read a Message?

In this case the solution is to re-send the message with a new key. Any attempt at message repair or error recovery would probably compromise the system.Q: What If You Can't Generate the Keys Fast Enough?

Add more hardware in parallel.Q: What If You Can Guess Some of the Source File Bits and Use This To Change the File?

This is a legitimate, known flaw of the method. Most file formats have a well-known structure. For example, a docx file is a zipped XML file, and a Zip archive has well-defined bits at the beginning, including: Version needed to extract (minimum) Compression method File last modification time and date If you can make a reliable guess what these values are, you can reverse-engineer the key bits for those bits. (It won't help you figure out the other bits in the key if they are truly random.) This would allow you to change the bits you know to something else, garbling the message or even changing its meaning. This is why the hash is added. It is extremely difficult (but not impossible) to change a file without changing the value of its hash, which would signal that tampering had occurred. ( en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hash_function )Q: If You're Going To All the Trouble To Hand-Deliver the Key Files On USB Drives, Why Not Just Hand-Deliver the Messages the Same Way Instead?

Good point, and that's not a bad idea, but you should be able to deliver the keys when it's convenient (as well as less frequently) and email the messages as needed.Q: Why Can't We Email the Keys?

Don't you dare.Q: What If Ninjas Sneak Into Your Headquarters and Copy the Keys?

Then they could just steal your computers and get all of your unencrypted data. (Quite a few of the objections to one time pads, rebutting the claim that the codes are unbreakable, seem to involve ninjas.)Q: How Does This Protect Against Hacks Like the Sony Breakin?

It wasn't designed to.Q: What About Quantum Computing?

Doesn't matter.Q: What If Ninjas Modify Your key-Generating System?

Enough with the ninjas!Q: Do You Have Anything Else To Add?

In an earlier, more naive version of this idea, I proposed using bit streams snatched from on-line sources like Jpeg files, which would certainly be strong encryption, but not uncrackable. ( www.well.com/user/abs/Crypto ) Notice that a offered a $20 prize for decrypting a message when I provided a hint to where to find the key, and a $2000 prize when there was no hint. I only distributed the message to a few friends, but someone reposted the challenge part of the file to an encryption newsgroup. I got some flack because it was such a short message, and these kinds of stunts are usually regarded as pointless. Nevertheless, I never had to pay the $2000 (or try to reneg). Unfortunately I forgot what the plaintext said, and I lost the key, so I suppose at this point I'll never know, unless I can recover the memory through hypnosis.The Political Component

James Madison, author of the Fourth Amendment in the Bill of Rights, as pictured on the $5000 bill (Lunatic Blog)

"I think people watch TV and think the bureau can do lots of things. We cannot break strong encryption." — FBI Director James Comey testifying to the US Senate Intelligence Committee on the need for law-enforcement "backdoors" to encryption, July 8, 2015( www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2015/07/08/421251662/fbi-director-says-agents-need-access-to-encrypted-data-to-preserve-public-safety ) First of all let me say that, sad as it makes me to admit this, I know that my ideas are controversial in this day and age. For example, I have a near, dear relation who is a flight attendant, and I'm pretty sure she wants terrorists stopped even if the Fourth Amendment gets shredded in the process. But I can't go for that. I believe that our founding fathers were quite wise (even if they didn't always practice what they preached), and there are good reasons to maintain and defend our constitutional rights. When James Madison wrote "The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated," I think that was meant to include email, texts, private web forums, and other electronic communications. Our government claims otherwise (when they bother to claim anything — much of the time they just snatch what they want secretly). I want to roll this back. It is still legal to encrypt your communications, though some in law enforcement keep trying to make a run at this right. During the early days of the Clinton administration a proposal called the "Clipper chip" would have mandated back doors for government spying in all electronic devices. Luckily it was shot down, but it keeps popping up with new names. For a while there they tried to shut down just talking about encryption, calling it "exporting munitions" if keys were 512 bytes or more. This has been eased, but you still have to tell the Bureau of Industry and Security, located about 1000 feet from the White House in Washington, if you want to release open source encryption software. ( en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Export_of_cryptography_from_the_United_States ) I believe one way to hold back the tide of encroachment is to get technology out there into citizens' hands while it's still easy. Recall the cautionary tale of dual key encryption, which barely missed being classified and buried because the inventors had the good sense to publish their work in Canada just in time. If you think it's too dangerous to give citizens superencryption technology (which, as I've said, is already in the public domain), here's something to consider. If your goal is fighting terrorists "at any cost" you can use that argument to justify all of these steps:

- opening everyone's mail and reading it

- tapping all phone calls without a warrant

- mounting government spy cameras in every room of every home

- randomly arresting and interrogating citizens

- torturing all suspects

- threatening to kill family members of uncooperative witnesses

Look For Us On Kickstarter

With recent events I have decided the time is right to go into production on this design. My current plan is to do a "Kickstarter" project to open source the hardware, and sell the software (in source code form) along with pre-built hardware for convenience. I'll publicize it here if you want to participate. One big part of the project will be to buy and comparison test hardware random number generators. ( en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comparison_of_hardware_random_number_generators ) We also plan to offer a cash prize for cracking the uncrackable, and hire some lawyers to try and stay out of trouble. Wish us luck.Feature:

"If It's Just a Virtual Actor,

Then Why Am I Feeling Real Emotions?"

(Part Six)

SERIOUS FUN

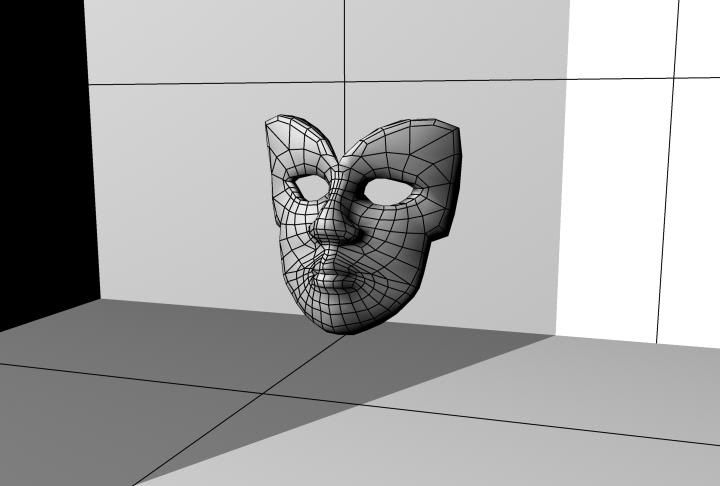

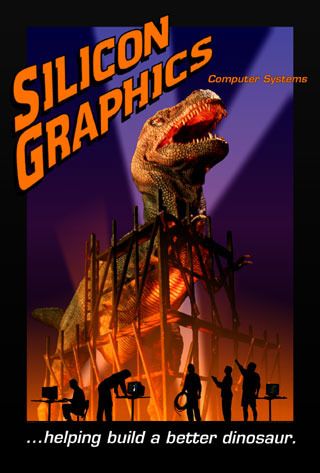

Silicon Graphics "Serious Fun" marketing, circa 1993

( www.nekochan.net/weblog/archives/2002/11/ )

Silicon Graphics "Serious Fun" marketing, circa 1993

( www.nekochan.net/weblog/archives/2002/11/ )

1993, second year in Anaheim. This is the year they had the virtual sex panel which, uh, everybody had a good time with. 1993 was also the year that had, what I think is probably the most amazing SIGGRAPH party that's ever happened, which was the party at the Richard Nixon Museum. I have this image of watching Timothy Leary ranting and raving on stage at the Nixon Museum, twenty feet from the grave of Pat Nixon, and it's... just really cosmic, I don't know. — Jim Blinn, "SIGGRAPH '98 Keynote"( www.siggraph.org/s98/conference/keynote/blinn.html ) There was something magical about SIGGRAPH '93 in Anaheim. There's more than I have space to relate here, but a few examples will suffice.

- Building a Better Dinosaur — 1993 was really Silicon Graphics Inc's year. About half a decade previously, at the same Anaheim Convention Center, I heard computer graphics conference keynote speeches by Robert Abel ( en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Abel_%28animator%29 ) and Roy E. Disney, ( en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roy_E._Disney ) telling us that "someday" CG would be used to do live-action movie effects. And now, SGI's computers had been used to do the first major photo-realistic computer animations in movie history, for Steven Spielberg's blockbuster hit "Jurassic Park." ( www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/B0087ZG7HK/hip-20 ) To celebrate they rented four full-sized trade show booths on the SIGGRAPH exhibit floor, and installed a theme park ride, complete with Jurassic Park jeeps. I didn't get to ride it since demand far outstripped supply, and I wasn't in the market for their hardware, so I didn't make the VIP list. (Although, not long afterwards, the company I worked for — Advanced Visual Systems (AVS) — bought an SGI Indigo 2 workstation and put it on my desk.) SGI also launched a marketing campaign around the phrase "serious fun," and printed a series of what looked like baseball cards showcasing the uses of their computers in showbiz.

- Van Dam Rex — About week before SIGGRAPH I had dropped in on an academic conference at nearby UC Irvine on the topic of visualization in education. In attendance was computer graphics pioneer Dr. Andres Van Dam, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andries_van_Dam co-author of the textbook on the subject I'd used in college. I had met him when he was on the Technical Advisory Board of a previous job of mine, Stellar Computer. (When I visited the headquarters in Newton, Massachusetts, they let me use his office since he was never there, off teaching at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island.) At the Irvine conference, which I only attended on the last day, I contradicted Dr. Van Dam during a feedback session. I said I wanted to offer a view from industry, and explained that we no longer needed a lot of graduates who knew how to write renderers; we needed experts in computer graphics applications: chemistry, material science, oil and gas exploration, 3D medical imaging, geographical displays, animation, kineseology, etc. He got visibly irate and said "I completely disagree!" It was a learning experience for me. I realized upon reflection that, especially for academic conferences, it is important to be there for the whole thing, to build community and relationships, and also that when offering a contradictory point of view, it is best to put a positive spin on it. Anyhoo, a week later I was standing outside of the Anaheim Convention Center at the beginning of SIGGRAPH, when I was approached by a group of Dr. Van Dam's graduate students, a few of whom I knew from an AVS connection. One of them said that he'd heard I'd angered Dr. Van Dam at the education conference, and gave me a high five. Then he pointed to a large button he was wearing, which had a T-rex, altered to have Dr. Van Dam's head, and the caption: "VAN DAM REX." Clearly there was some dynamic at work here that I hadn't quite appreciated. (I'm proud to say that I saw Dr. Van Dam two years ago at a SIGGRAPH Pioneers banquet, and he claims to remember me positively, so either he's placed the incident behind him or, more likely, forgotten all about it.)

- Birds of a Feather Flock Together — Shortly before SIGGRAPH I was contacted by an academic named Benjamin H. Bratton, who I hadn't heard of before. ( en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benjamin_H._Bratton ) I have no idea how he found me, though I was developing a reputation as someone who liked to speak at conferences, and showed up on time with something to say, amusing if not enlightening. He invited me to speak at a panel he'd organized, called "Electronic Image and Popular Discourse." Being a fan of McLuhan's distinction of literary vs. oral cultures, I prepared some remarks I entitled "Hypertext or Game Boy: We Are At a Fork In the Road," looking at the important role going forward of good old alphabetical text in computer interactions. It was fun and educational, and I met some nice, smart folks, but an important take-home lesson was this: at the time (but no longer) any SIGGRAPH attendee could organize a "Birds of a Feather" (BoF) session and be assigned a room and listed in the program. The people who attended did not have to show a SIGGRAPH badge (which was always fairly expensive to get). This is what Benjamin had done for his "panel." Instead of submitting a proposal and awaiting the decision of a jury, he was able to create this sub-event by fiat. I learned from his example, and used this lesson in subsequent years.

- Next Year in Orlando — One of my traditions at the SIGGRAPH conference is to visit the booth for next year's conference, as early as possible during the show, and get a pin and a poster for the following year. (They usually ran out quickly.) That year the pin and poster showed a stylized nautilus shell, and advertised the conference a year away in Orlando, Florida — the first to be held there. SIGGRAPH was staking a claim for the invasion of theme park entertainment by computer graphics technology, and many of us were salivating at the chance to participate.

- Subsurface Scattering — They say it takes more than a day to understand the events of a day, and this was true of the handful of days of the SIGGRAPH 1993 conference. The conference proceedings ended up having impacts moving forward for quite some time. ( www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/0201588897/hip-20 ) I encountered several examples of this, but I'll share one that I have better recall of, because I blogged about it before. At SIGGRAPH 2003, ten years later, there was a presentation on the skin rendering in the movie "Shrek" (2001), ( www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/B0039N74CW/hip-20 ) which was one of the first feature films to do human skin well. The presenter said the tricky thing was that skin had multiple layers, and a good amount of water, and simulating how they reflected light was non-trivial. (This is why movie makeup was invented, because under the bright lights cameras used to need, deep layers of skin would become more visible and look strange.) He explained that the mathematics was worked out in the 1930s, but the first use in computer graphics was described in a paper published in the proceedings of SIGGRAPH 1993. ( www.creativeplanetnetwork.com/news/news-articles/skin-deep/383131 )

SUCH HILARITY AND MIRTH

The Bonzo Dog Band on

"Do Not Adjust Your Set" (BBC)

Late in the summer of 1993 I decided I wanted to do something to stay in touch

with Anne Herring. One of the shows she'd performed at the Adventurers Club

was called the "Maid's Singalong," done in character as Ginger Vitus the maid.

She worked the room alone (except for her invisible accompanist, Fingers the

ghost of the keyboard player). She sang some songs, lead the crowd in some

singing, and even encouraged a few brave guests to stand up and perform songs

they knew. (Going through various evolutions, this show continued to be

performed until the bitter end of the club.)

( www.youtube.com/watch?v=T3Z5msSkDEw )

In the spirit of this show, I made a short mix tape — of two songs — that

I thought would be great in the club, "Mad Dogs and Englishmen Go Out in the

Midday Sun" by Noel Coward (1932),

( www.youtube.com/watch?v=z2YvYiWtovM )

and "Hunting Tigers Out In Indiah" performed by the Bonzo Dog Band (1969),

a cover of a 1930 song by Hal Swain & His Band.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZNmL1L3dF6g

( www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZNmL1L3dF6g )

I was able to mail her the cassette, since we'd talked her out of her postal

address. Later she told us she was familiar with the Noel Coward song, but

not the Bonzo Dog Band one. (An aside: the above video of the Hunting Tigers

song is actually from a rare BBC program for children, "Do Not Adjust Your Set,"

which starred several comedians who later went on to fame in the troupe Monty

Python's Flying Circus.)

( en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Do_Not_Adjust_Your_Set )

The Bonzo Dog Band on

"Do Not Adjust Your Set" (BBC)

Late in the summer of 1993 I decided I wanted to do something to stay in touch

with Anne Herring. One of the shows she'd performed at the Adventurers Club

was called the "Maid's Singalong," done in character as Ginger Vitus the maid.

She worked the room alone (except for her invisible accompanist, Fingers the

ghost of the keyboard player). She sang some songs, lead the crowd in some

singing, and even encouraged a few brave guests to stand up and perform songs

they knew. (Going through various evolutions, this show continued to be

performed until the bitter end of the club.)

( www.youtube.com/watch?v=T3Z5msSkDEw )

In the spirit of this show, I made a short mix tape — of two songs — that

I thought would be great in the club, "Mad Dogs and Englishmen Go Out in the

Midday Sun" by Noel Coward (1932),

( www.youtube.com/watch?v=z2YvYiWtovM )

and "Hunting Tigers Out In Indiah" performed by the Bonzo Dog Band (1969),

a cover of a 1930 song by Hal Swain & His Band.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZNmL1L3dF6g

( www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZNmL1L3dF6g )

I was able to mail her the cassette, since we'd talked her out of her postal

address. Later she told us she was familiar with the Noel Coward song, but

not the Bonzo Dog Band one. (An aside: the above video of the Hunting Tigers

song is actually from a rare BBC program for children, "Do Not Adjust Your Set,"

which starred several comedians who later went on to fame in the troupe Monty

Python's Flying Circus.)

( en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Do_Not_Adjust_Your_Set )

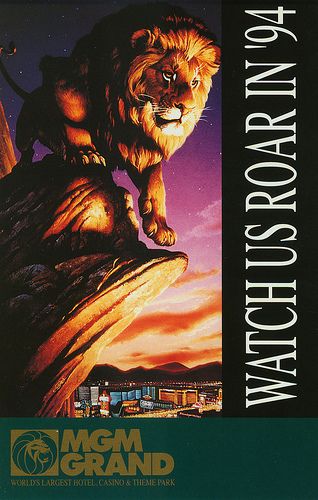

WATCH US ROAR IN '94

"Bug, Sig and Karla were all a bit annoyed by how 'family-oriented' and we yearned for traces of its proud history of sleaze and corruption. I mean, if you can't get lost in Las Vegas then what's the point of Las Vegas?" — Douglas Coupland, 1995 "Microserfs"( www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/0061624268/hip-20 ) I've been a fan of Preview Centers for a long time. I think my first one was the Walt Disney World Preview Center, which our aunt, uncle and cousins took us to when our family visited Florida in the summer of 1971, just a few months too soon to visit the Magic Kingdom. Later I also greatly enjoyed the Disney's California Adventure Preview Center, located near the Disneyland ticket booths, which in some ways was better than the finished theme park. But the world record for preview centers must be held by Las Vegas in the 1990s. Amid well-videotaped casino implosions (most of which can be found on YouTube), ( www.youtube.com/watch?v=5igVwiXk-gM ) Sin City was working hard to reinvent itself at that time, and I remember visiting trailers with concept art, models, and advance souvenirs for sale for at least three new casino/resorts: the New York New York, the Aladdin, and the MGM Grand. In each case I bought a t-shirt, and for a while I considered it to be a techie status symbol (with time travel overtones) to wear a shirt for a casino that was in the future. (I got a copy of the poster above at the MGM Grand Preview Center in 1993.) During this heady era the SIGGRAPH conference came to Las Vegas its one and only time, in the summer of 1991, and several computer graphics vendors took advantage of the opportunity to do a hard court press with casino managers, pitching ideas for Virtual Reality (VR) and other eye candy to the leaders of the gambling empire. I can't show cause and effect, but a great deal of cutting edge "new media" style spectacle — what they used to call "location-based entertainment" — popped up in Vegas. There was the Pharaoh illusion in front of the Luxor, the audio-animatronic dragon that emerged from the Excalibur, only to be vanquished by Merlin the Wizard, and eventually an authentic Virtual Actor in the form of a computer-generated pirate which had live conversations with folks entering the Treasure Island casino from the parking garage and riding down an escalator. (The latter was not very effective; the phenomenon lasted such a short time on the escalator ride that very few guests realized it was a live, interactive character.) Along with this new tech revolution there was also a general trend of Las Vegas attempting to become more family friendly. Along with a Wizard of Oz theme, there were lions in lobby of the MGM Grand. The Mirage had the white tigers from the Siegfried and Roy show on display in their lobby, and a dolphin garden out back. The afore-mentioned Treasure Island had a live pirate ship battle with a British man o' war every hour in the false bay at the front of the casino. The Luxor had a whole level in its pyramid of family-friendly movie/rides and a world class Sega arcade. The Excalibur also had a whole level of carnival-style games, puppet shows, medieval fantasy crafts, and not a gambling machine in sight. In the basement was a jousting dinner show, much like Medieval Times near Disneyland in California and Walt Disney World in Florida. Circus Circus and the MGM Grand added full-up amusement parks out back. New York New York had a roller coaster running right through the Manhattan skyline facade. Also right on "the strip" Coca Cola and M'n'Ms built museums, and the DreamWorks-inspired GameWorks opened an arcade. (My all-time favorite Vegas attraction was Star Trek: the Experience, which I can't say enough good things about.) ( en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Star_Trek:_The_Experience ) In addition to these attractions at A-list locations, other lesser venues spent big to attract families with kids, including casinos at State Line on the California-Nevada border, which had the advantage of being the first legal gambling drivers came to when arrive on Interstate 15 from the Los Angeles area. Buffalo Bill's built a water ride, amusement area, and possibly the scariest roller coaster I've ever ridden, while the Primadonna next door had a ferris wheel out front and a merry-go-round and arcade in a basement level. This dream came crashing down in 1997 when a seven year old girl, left unattended by her gambling father, was murdered near that merry-go-round. ( articles.latimes.com/1997-05-28/news/mn-63101_1_casino-surveillance ) The casino management was so mortified they changed the name to the Primm to escape the bad publicity, and ripped out the rides and attractions. The businesses of Las Vegas did some soul searching, admitted that gambling-obsessed parents leaving their kids unattended was in fact a big problem, and backed away from the family-friendly image. A subsequent national TV ad campaign was "What Happens in Vegas Stays in Vegas," and the town went back to being Sin City.

STAYING IN THE GAME

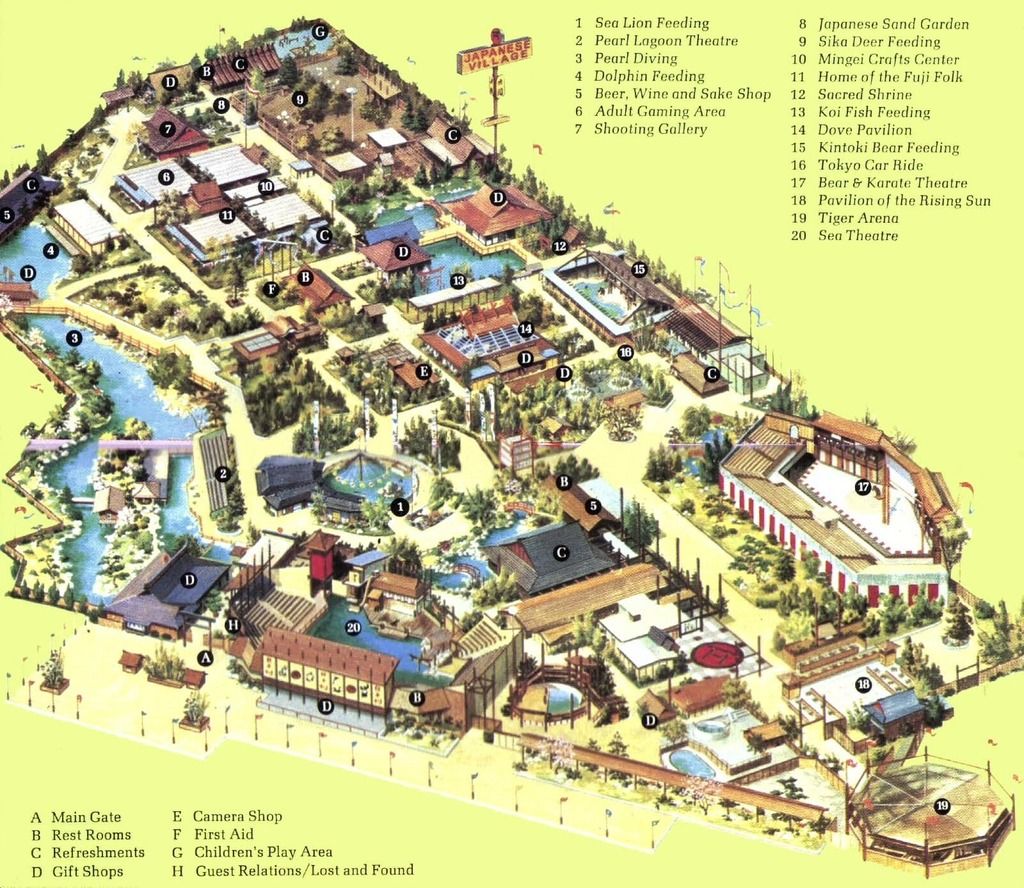

map of Japanese Village and Deer Park

( ochistorical.blogspot.com/2010/06/buena-park-brea-and-oc-railroads.html )

map of Japanese Village and Deer Park

( ochistorical.blogspot.com/2010/06/buena-park-brea-and-oc-railroads.html )

D: You just bring that right on, right on up then, uhh? L: Alright, where do you want me to deliver it? D: Up at my house L: Where do you live? D: Up on the north side L: On the north side D: Ya L: Whereabouts on the north side? D: Up there by the Japanese amusement park L: The Japanese amusement park D: Bambi's deer place there L: Is that right? D: Where Bambi goes, nothin' grows — Hudson & Landry "Ajax Liquor Store" (audio comedy)( www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/B000069Z0U/hip-20 ) Despite the fact that I was involved with two previous computer game projects which ended badly, in late 1993 I again was bitten by the game design bug, and decided I wanted to create a new game design. (I wasn't so keen to implement, so my goal was a design document.) I mentioned this inclination to Steve Tice, my old boss from Rockwell who had gone on to lead the company, Simgraphics, that invented the Virtual Actor and Performance Animation, and who at that point was managing computer game developers. He said he wanted to encourage my efforts. By way of inspiration he took me to the International Association of Amusement Parks and Attractions (IAAPA) conference at the Los Angeles Convention Center in November of 1993. ( www.iaapa.org ) The L.A. Times reported that over 25,000 people attended that year. ( articles.latimes.com/1993-12-03/local/me-63347_1_convention-attendance-los-angeles ) Steve especially wanted me to see the "VR aisle" that year — in addition to the traditional vendors selling carnival-type rides, water park equipment, game prizes, liability insurance, popcorn machines, etc., this new category featured "motion-base" rides, innovative interactive games, and other "new tech" solutions to the age-old problem of amusing the Rubes. Well, I was impressed with the technology and the business opportunities, and Steve and I agreed to begin having a series of informal discussions. We ended up having a series of very interesting conversations, often in places that provided additional stimulation for our ideas. One place we visited several times was Beach Boulevard in Buena Park, the street that Knott's Berry Farm was on. I had read in a newspaper article that a two-block stretch of this street had the largest concentration of separate amusements — location-based entertainment venues if you will — found anywhere in America. Historically this street had been home to some almost legendary roadside amusements, including the above-pictured Japanese Deer Park, ( www.ocregister.com/articles/park-608019-deer-museum.html ) as well as a whole menagerie of other oddities, including famous and infamous extinct attractions such as:

- Jungle Island

- Movie World/Cars of Stars/Planes of Fame Museum

- California Alligator Farm

- Wild Bill's Wild West Dinner Extravaganza

- Kingdom of Dancing Stallions (home of the world-famous Lipizzaner Stallions, which were brought to America from Vienna, and later moved into the Excalibur in Las Vegas)

- Movieland Wax Museum

- Knott's Independence Hall

- Pirate's Dinner Adventure

- Medieval Times

- Ripley's Believe It Or Not Museum

- Mott's Miniatures & Dollhouse Shop

- Museum of World Wars

- a McDonald's with a motion-base ride

- Po' Folks Restaurant with a model train running through it

SCREWING UP MY COURAGE

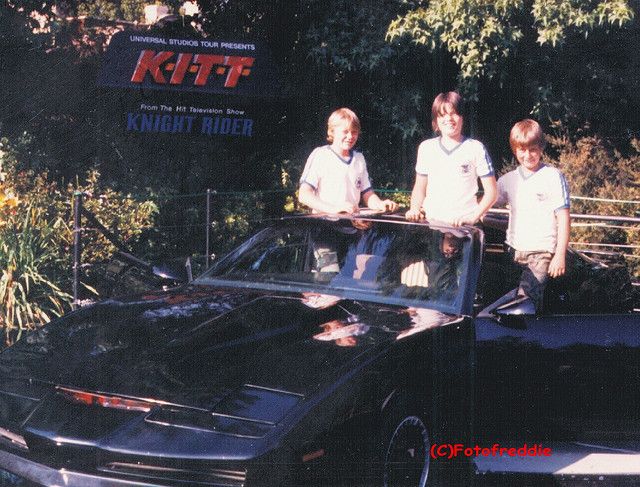

Kitt Car at Universal Studios Hollywood

I think it might have been New Years Eve 1993/94 that I met Richard Cray; if

not then shortly afterwards. We were introduced by my friend Greg Panos, who

as I mentioned previously is a supernode in the social network. Richard is an

actor, and had been performing in New York in "The Mystery of Edwin Drood," an

interactive production in which the audience helps write the ending. He had

come to Los Angeles because he wanted to become an operator of Virtual Actor

and Performance Cartoon technology. Richard sought out Greg because of his

fame in the VR community, and Greg offered him a place to stay as he chased

his dream on the Left Coast. (Twenty-one years later they are still roommates.)

As 1994 began I was looking ahead to the SIGGRAPH conference coming up in

Orlando. Many of the deadlines for papers, panel, courses, etc. are in

mid-January. I had been thinking about interactive media, Virtual Actors,

and their connection to the Adventurers Club. Though the club didn't use any

technology more advanced than puppets, the actors there had been racking up

close to five years of experience entertaining real audiences with interactive

entertainment. I wanted to find some kind of synergy between their skills

and experience and those of the computer graphics community.

In one of our early conversations I shared with Richard this idea, and he

was wildly enthusiastic. He had recently been doing performance animation gigs

for Simgraphics Corporation, and said he wanted to participate in whatever

event I organized. I was leaning towards a panel, but then realized I should

instead do a Birds of a Feather (BoF) session, as Benjamin Bratton had taught

me at SIGGRAPH 1993. This wold easier, and I would have more time to pull it

together, since the BoF deadline was much later. At some point I came up with

the title, "The VActor and the Human Factor."

Then I had a crisis of confidence. I didn't have as much faith then as I do

now in my ability to make things happen. I almost chickened out, despite

Richard's encouragement. When I shared the idea with Steve Tice he was also

enthusiastic, though he wasn't willing to commit to participate. He did

suggest I involve Brad de Graf, of De Graf-Wahrman fame, who had done

early experiments with Jim Henson with an interactive wire-frame Kermit the

Frog on an Evans and Sutherland vector-based graphics system, and offered to

make an introduction for me.

Still I dithered. I decided I needed to work on screwing up my courage.

I had an annual pass to Universal Studios Hollywood, and they had a small

attraction there which consisted of the "Kit Car" from the TV show "Knight

Rider" (1982-86), about a spy name Michael, played by David Hasselhoff,

who drove a superintelligent computer-controlled car named Kit.

( www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/B00005JLG4/hip-20 )

Guests could sit in the car and talk to the computer. A voice actor (not of

course the original star William Daniels, of "A Thousand Clowns" fame) provided

the interactive voice of the car from an unseen location.

As I related in C3M volume 4 number 8:

Kitt Car at Universal Studios Hollywood

I think it might have been New Years Eve 1993/94 that I met Richard Cray; if

not then shortly afterwards. We were introduced by my friend Greg Panos, who

as I mentioned previously is a supernode in the social network. Richard is an

actor, and had been performing in New York in "The Mystery of Edwin Drood," an

interactive production in which the audience helps write the ending. He had

come to Los Angeles because he wanted to become an operator of Virtual Actor

and Performance Cartoon technology. Richard sought out Greg because of his

fame in the VR community, and Greg offered him a place to stay as he chased

his dream on the Left Coast. (Twenty-one years later they are still roommates.)

As 1994 began I was looking ahead to the SIGGRAPH conference coming up in

Orlando. Many of the deadlines for papers, panel, courses, etc. are in

mid-January. I had been thinking about interactive media, Virtual Actors,

and their connection to the Adventurers Club. Though the club didn't use any

technology more advanced than puppets, the actors there had been racking up

close to five years of experience entertaining real audiences with interactive

entertainment. I wanted to find some kind of synergy between their skills

and experience and those of the computer graphics community.

In one of our early conversations I shared with Richard this idea, and he

was wildly enthusiastic. He had recently been doing performance animation gigs

for Simgraphics Corporation, and said he wanted to participate in whatever

event I organized. I was leaning towards a panel, but then realized I should

instead do a Birds of a Feather (BoF) session, as Benjamin Bratton had taught

me at SIGGRAPH 1993. This wold easier, and I would have more time to pull it

together, since the BoF deadline was much later. At some point I came up with

the title, "The VActor and the Human Factor."

Then I had a crisis of confidence. I didn't have as much faith then as I do

now in my ability to make things happen. I almost chickened out, despite

Richard's encouragement. When I shared the idea with Steve Tice he was also

enthusiastic, though he wasn't willing to commit to participate. He did

suggest I involve Brad de Graf, of De Graf-Wahrman fame, who had done

early experiments with Jim Henson with an interactive wire-frame Kermit the

Frog on an Evans and Sutherland vector-based graphics system, and offered to

make an introduction for me.

Still I dithered. I decided I needed to work on screwing up my courage.

I had an annual pass to Universal Studios Hollywood, and they had a small

attraction there which consisted of the "Kit Car" from the TV show "Knight

Rider" (1982-86), about a spy name Michael, played by David Hasselhoff,

who drove a superintelligent computer-controlled car named Kit.

( www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/B00005JLG4/hip-20 )

Guests could sit in the car and talk to the computer. A voice actor (not of

course the original star William Daniels, of "A Thousand Clowns" fame) provided

the interactive voice of the car from an unseen location.

As I related in C3M volume 4 number 8:

"I once met a comic (teaching traffic school) who claimed that his first job in Hollywood was the voice of Kitt; he said the guests all asked, 'Where's Michael?' all day long."( www.well.com/user/abs/Cyb/archive/c3m_0408.html ) (As it turned out, when I met him again he admitted he'd made up the story for comic effect. Oh well.) Anyway, I used this attraction as a laboratory of interactive entertainment. I would go to Universal and sit, sometimes for hours, watching and listening as guests young and old interacted with the car. And as I learned and observed, I worked on pumping myself up. Later I got an annual pass to Knott's Berry Farm, which at the time had a themed "land" called "Knott's Airfield." (It had originally been the "Gypsy Camp," then the "Roaring 20s," and after the airfield theme it became the "Boardwalk," which is now where most of the big iron thrill rides are located.) I found the 1920s airfield theme to be quite charming. There was a restaurant there called Captain Kelly's which I enjoyed, next to the Wacky Soap Box Racers, which were taken out two years later. When I finally decided to "go for it" and organize the BoF/panel for SIGGRAPH, I would go to Captain Kelly's and sit enjoying boysenberry pie and coffee while working on the paperwork: letters to Brad de Graf, the Adventurers Club actors, and imagineer Joe Rhode, who helped design the club, and application forms to the 1994 SIGGRAPH committee. I enjoyed the ambience as my reward for sticking with the task, which I still had some resistance to completing.